Research by Aazim Bill SE Yaswant and Nipun Gupta

While some financially motivated scams may seem simple on the surface, the truth of the matter is that cybercriminals are investing large amounts of money into strategies and infrastructure to scale up their malicious campaigns. Those investments are paying off as threat actors continue to target mobile users with successful campaigns.

In October, the Zimperium zLabs team informed the community about GriftHorse, a massive mobile premium service abuse campaign that compromised around 10 million victims globally. In the pursuit of identifying and taking down similar financially motivated scams, zLabs researchers have discovered another premium service abuse campaign with upwards of 105 million victims globally, which we have named Dark Herring. The total amount of money scammed out of unsuspecting users could once again be well into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

These malicious Android applications appear harmless when looking at the store description and requested permissions, but this false sense of confidence changes when users get charged month over month for premium service they are not receiving via direct carrier billing. Direct carrier billing, or DCB, is the mobile payment method that allows consumers to send charges of purchase made to their phone bills with their phone number. Unlike many other malicious applications that provide no functional capabilities, the victim can use these applications, meaning they are often left installed on the phones and tablets long after initial installation.

Threat intelligence on the active Dark Herring Android Scamware campaign revealed that the date of publication of the apps dates back to March 2020. To date, Dark Herring is the longest-running mobile SMS scam discovered by the Zimperium zLabs team.

These malicious applications were initially distributed through both Google Play and third-party application stores. Zimperium zLabs reported the findings to both Google and the web hosts, who verified the provided information and removed the malicious materials as part of a coordinated takedown. At the time of publishing, the scam services and phishing sites are no longer active, and Google has removed all the malicious applications from Google Play.

However, the malicious applications are still available on third-party app repositories, once again highlighting the risk of sideloading applications to mobile endpoints and the need for advanced on-device security.

Disclosure: As a key member of the Google App Defense Alliance, Zimperium scans applications before they are published and provides an ongoing analysis of Android apps in the Google Play Store.

In this blog, we will:

- Cover the capabilities of the scamware;

- Discuss the architecture of the applications;

- Show the communication with the C&C server; and

- Explore the global impact of this campaign.

Summary of Dark Herring Android Scamware

The Dark Herring mobile applications pose a threat to all Android devices by functioning as a scamware that subscribes users to paid services, charging an average monthly premium of $15 USD per month. This campaign has targeted millions of users from over 70 countries by serving targeted malicious web pages to users based on the geo-location of their IP address with the local language. This social engineering trick is exceptionally successful and effective as users are generally more comfortable with sharing information to a website in their local language.

Upon infection, the Dark Herring-infected application communicates with the C&C server, exposing the victim’s IP address. Based on the geolocation of the IP address, the decision to target the victim for Direct Carrier Billing subscription or not is taken by using server-side logic. The malware redirects the victim to a geo-specific webpage where they are asked to submit their phone numbers for verification. But in reality, they are submitting their phone number to a Direct Carrier Billing service that begins charging them an average of $15 USD per month. The victim does not immediately notice the impact of the theft, and the likelihood of the billing continuing for months before detection is high, with little to no recourse to get one’s money back.

The threat actors responsible for Dark Herring generated and published almost 470 applications on the Google Play Store over a long period, with the earliest submission dating to March 2020 and as recently as November 2021. The number of applications attributed to this campaign indicates that the motivated and persistent threat actors are continuously scaling up their architecture and resources to infect as many victims as possible to maximize their gains.

Zimperium zLabs researchers have noticed a pattern in the C&C communication, which suggests that the threat actors have developed an infrastructure to handle the communication coming from several applications with unique identifiers and responding accordingly.

The download statistics reveal that more than 105 million Android devices had this scamware installed, potentially falling victim to this campaign globally, possibly suffering incalculable financial losses. The cybercriminal group behind this campaign has built a stable cash flow of illicit funds from these victims, generating millions in recurring revenue each month, with the total amount stolen potentially well into the hundreds of millions.

How does the Dark Herring Android Scamware work?

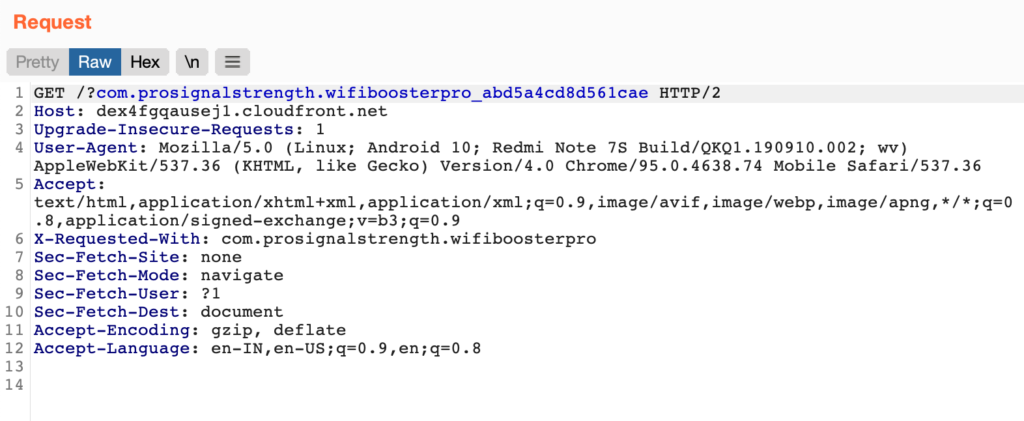

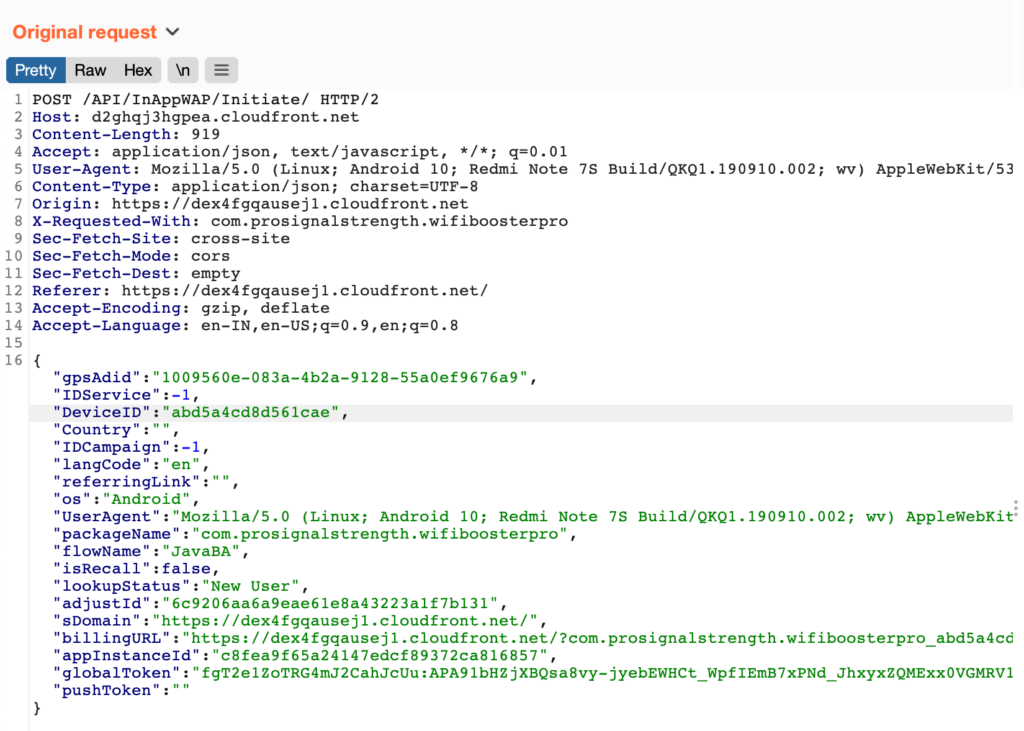

Once the Android application is installed and launched, a URL that acts as the first-stage endpoint is loaded into a webview. The URL can be retrieved from a hard-coded string, the resource strings, or decrypting a string. The first-stage URL is always an endpoint hosted on Cloudfront. The initial GET request sent to the Cloudfront URL is shown in Figure 1.

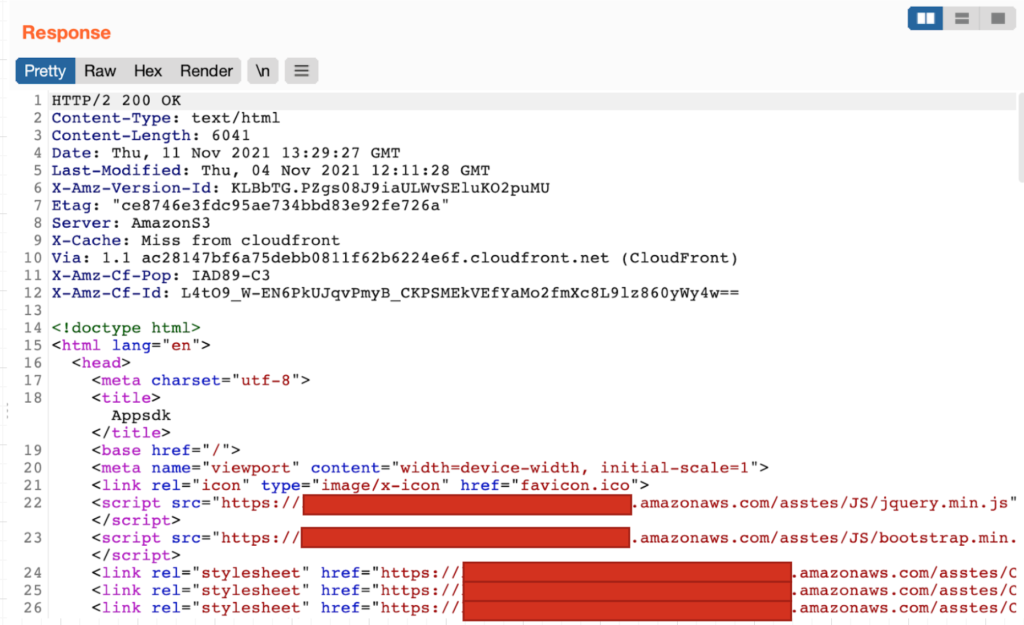

The response contains the links to JavaScript files hosted on AWS instances, and the application fetches all the resources to proceed with the infection process, as shown in Figure.2.

One of such JS files instructs the application to get a unique identifier for the device by making a POST request to the “live/keylookup” API endpoint and then constructing a final-stage URL.

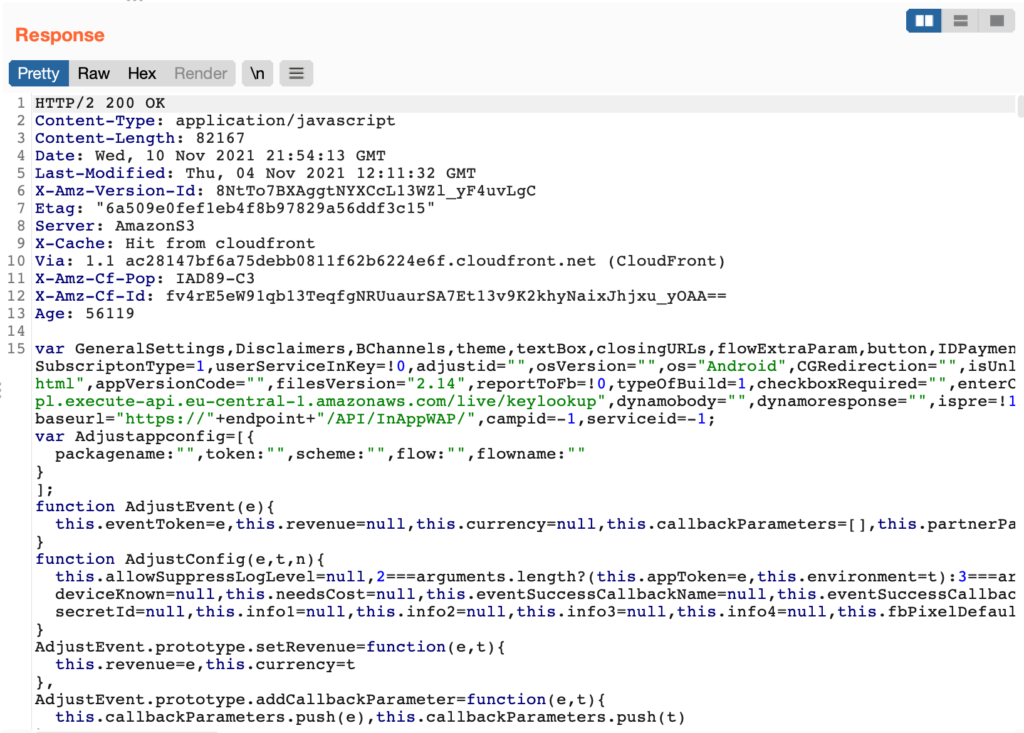

The baseurl variable, as seen in Figure 3, is used to make a POST request that contains unique identifiers created by the application to identify the device and the language and country details.

The response from the above endpoint contains the configuration for the application’s behavior based on the victim’s details. A list of supported countries is found in the response that indicates the targeted citizens of countries will be subject to subscription of the Direct Carrier Billing.

Based on the configuration, the webpage displayed to the victim gets customized in terms of the language of the text, flag, and country code.

The Threat Actors

Despite the similarities in approach between this campaign and GriftHorse, the Zimperium zLabs researchers have attributed this campaign to a new group of threat actors unaffiliated with the GriftHorse attackers. Several differences in the core codebase and other indicators are unique to this campaign, along with infrastructure investments not seen before. The level of sophistication, use of novel techniques, and determination displayed by the threat actors has allowed them to have such a large distribution around the world.

The Dark Herring campaign is one of the most extensive and successful malware campaigns by measure of the sheer number of applications that the zLabs threat research team has witnessed in 2021. Its success is attributed mainly to the rarely seen combination of several features:

- Novel techniques undetected by any other AV vendors

- Around 470 scamware applications were used in the campaign

- Use of proxies as first-stage URLs

- The geolocation of the users based on IP is used to identify potential victims.

- Vetting of application users to identify potential victims

- Using a sophisticated architecture to obfuscate the true intent

Producing a large number of malicious applications and submitting them to app stores points to an extensive, concerted effort by a well-organized group. These apps are not just clones of each other or other apps but are uniquely produced at a high rate to deceive traditional security toolsets and the potential victims.

The commonality of the malicious code and where the apps connect to it is more often than not the only common facet among the over 470 applications. The evidence also points to a significant financial investment from the malicious actors in building and maintaining the infrastructure to keep this global scam operating at such a high pace.

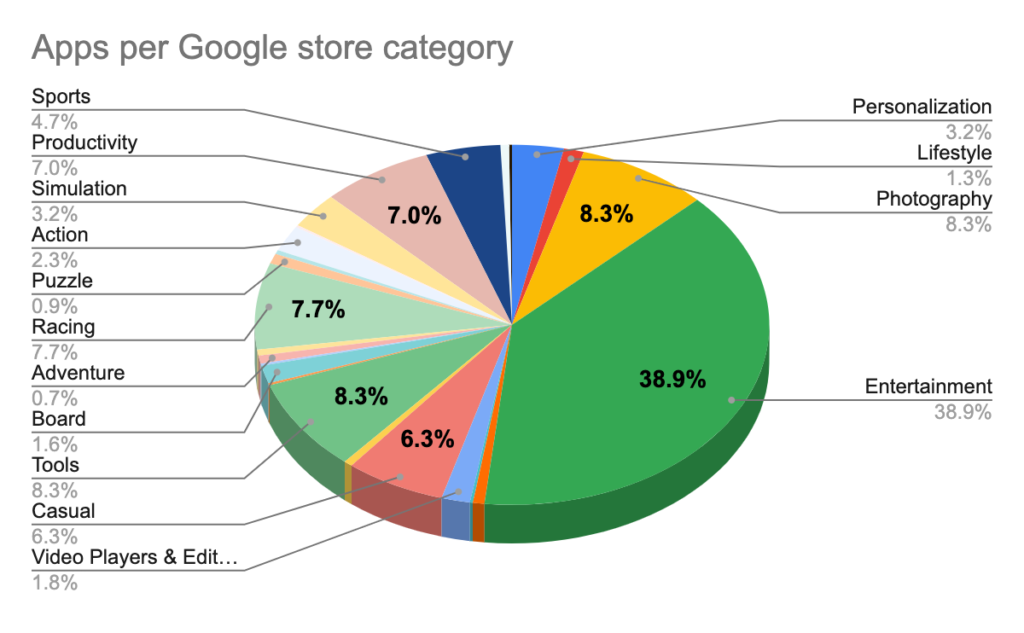

In addition to over 470 Android applications, the distribution of the applications was extremely well-planned, spreading their apps across multiple, varied categories, widening the range of potential victims. The apps themselves also functioned as advertised, increasing the false sense of confidence.

The Victims of Dark Herring Scamware

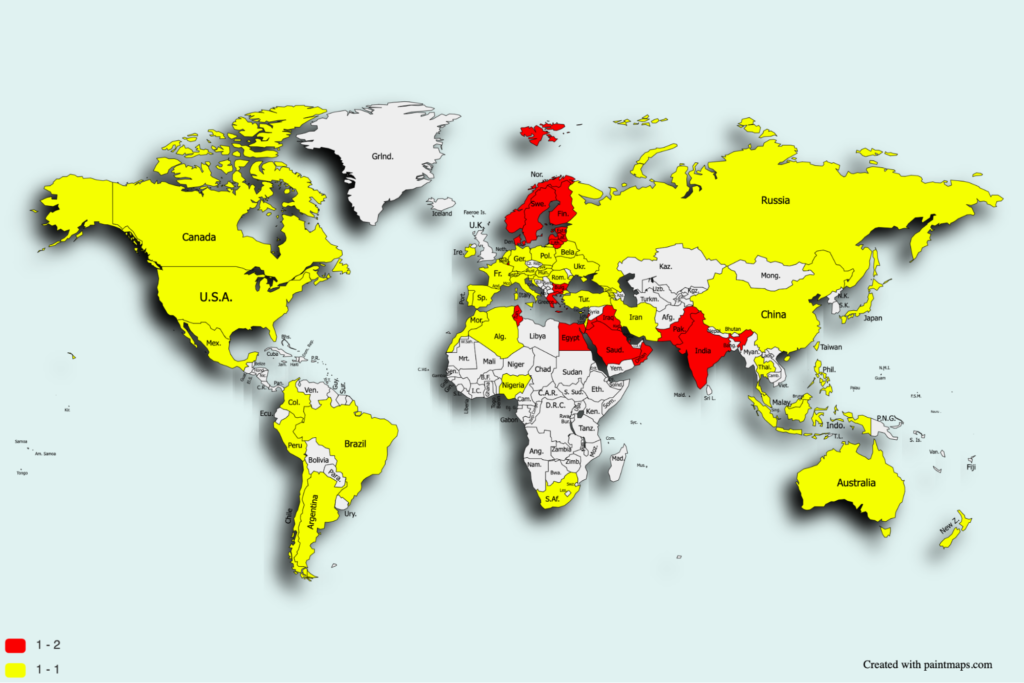

The campaign is exceptionally versatile, targeting mobile users from 70+ countries by changing the application’s language and displaying the content according to the current user’s IP address. Due to the nature of Direct Carrier Billing, some countries might have been targeted with less success than others due to the consumer protections set in place by telcos. Based on the collected intel, the Zimperium zLabs team estimates that Dark Herring has attempted to infect over 105 million devices since March 2020. In the map below, 70 countries have been identified with targeted victims. In the map below, nations highlighted in red have the highest risks to victims due to the lack of consumer protects from these types of Direct Carrier Billing scams.

Zimperium vs. Dark Herring Android Scamware

Zimperium zIPS customers are protected against the Dark Herring Scamware through the on-device malware detection, anti-phishing layers, and machine learning engine with the complete Zimperium mobile threat defense solution. Powered by the on-device z9 Mobile Threat Defense machine learning engine, customers can remain confident against this family of scams.

Zimperium on-device phishing classifiers detect the traffic from the malicious domains with our machine learning-based technology, blocking all traffic and preventing attackers from redirecting a potential victim to a targeted phishing site.

All the compromised and malicious applications found were also reviewed using Zimperium’s app analysis platform, z3A. The apps returned reports of high privacy and security risks to the end-user. Zimperium administrators can create risk policies preventing users from installing high-risk apps like Dark Herring.

To ensure your Android users are protected from Dark Herring Scamware, we recommend a quick risk assessment. Any application with Dark Herring will be flagged as a “Suspicious App Threat” on the device and in the zConsole. Admins can also review which apps are sideloaded onto the device that could be increasing the attack surface and leaving data and users at risk.

Indicators of Compromise:

The IOCs can be found in the following Github repository: https://github.com/Zimperium/DarkHerring

About Zimperium

Zimperium provides the only mobile security platform purpose-built for enterprise environments. With machine learning-based protection and a single platform that secures everything from applications to endpoints, Zimperium is the only solution to provide on-device mobile threat defense to protect growing and evolving mobile environments. For more information or to schedule a demo, contact us today.